A Magic Archive of Light and Glass

The Museo del Precinema in Padova illuminates the forgotten universe of magic lanterns, fascinating devices at the origin of motion pictures.

A mahogany box in the attic

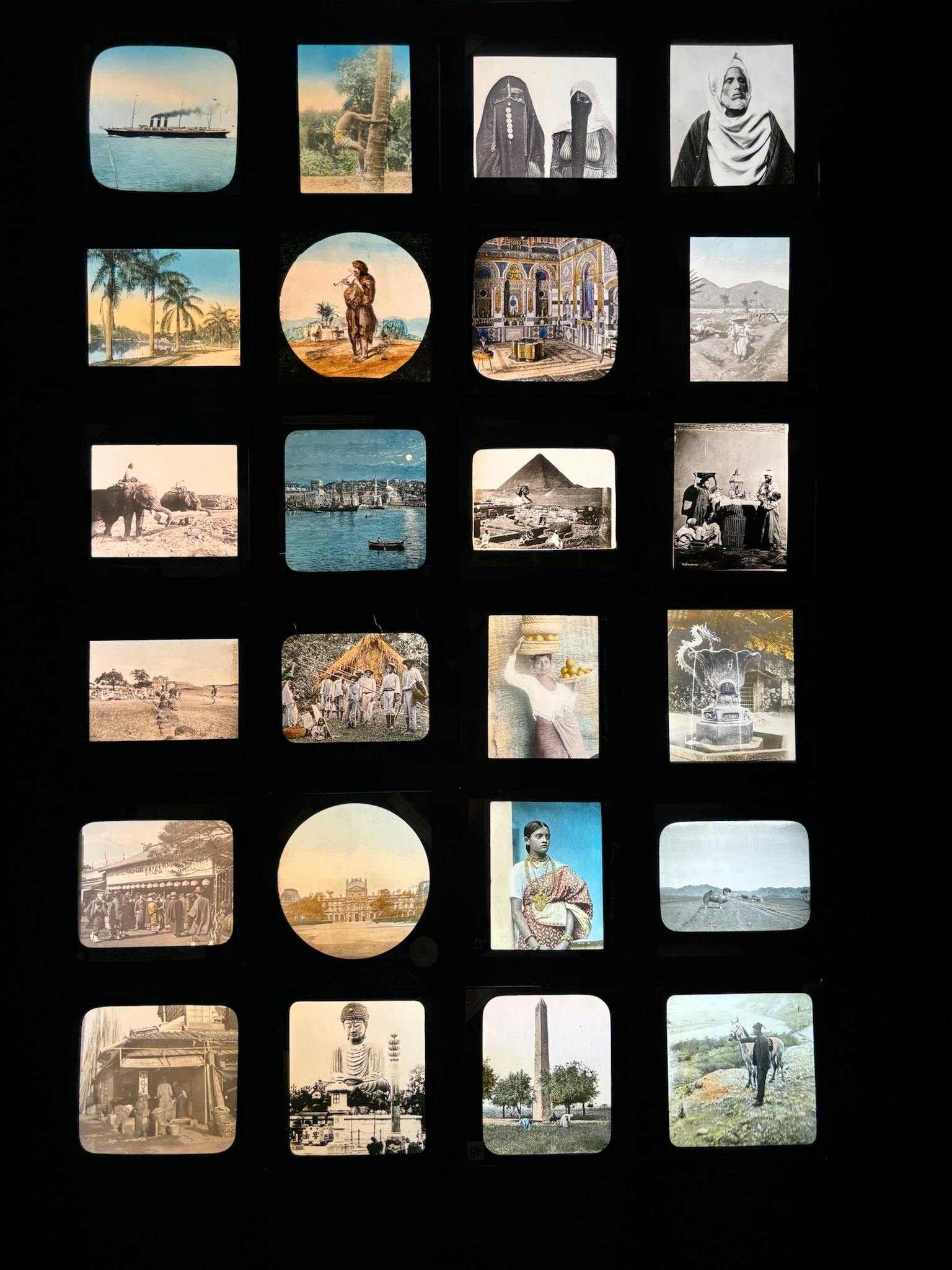

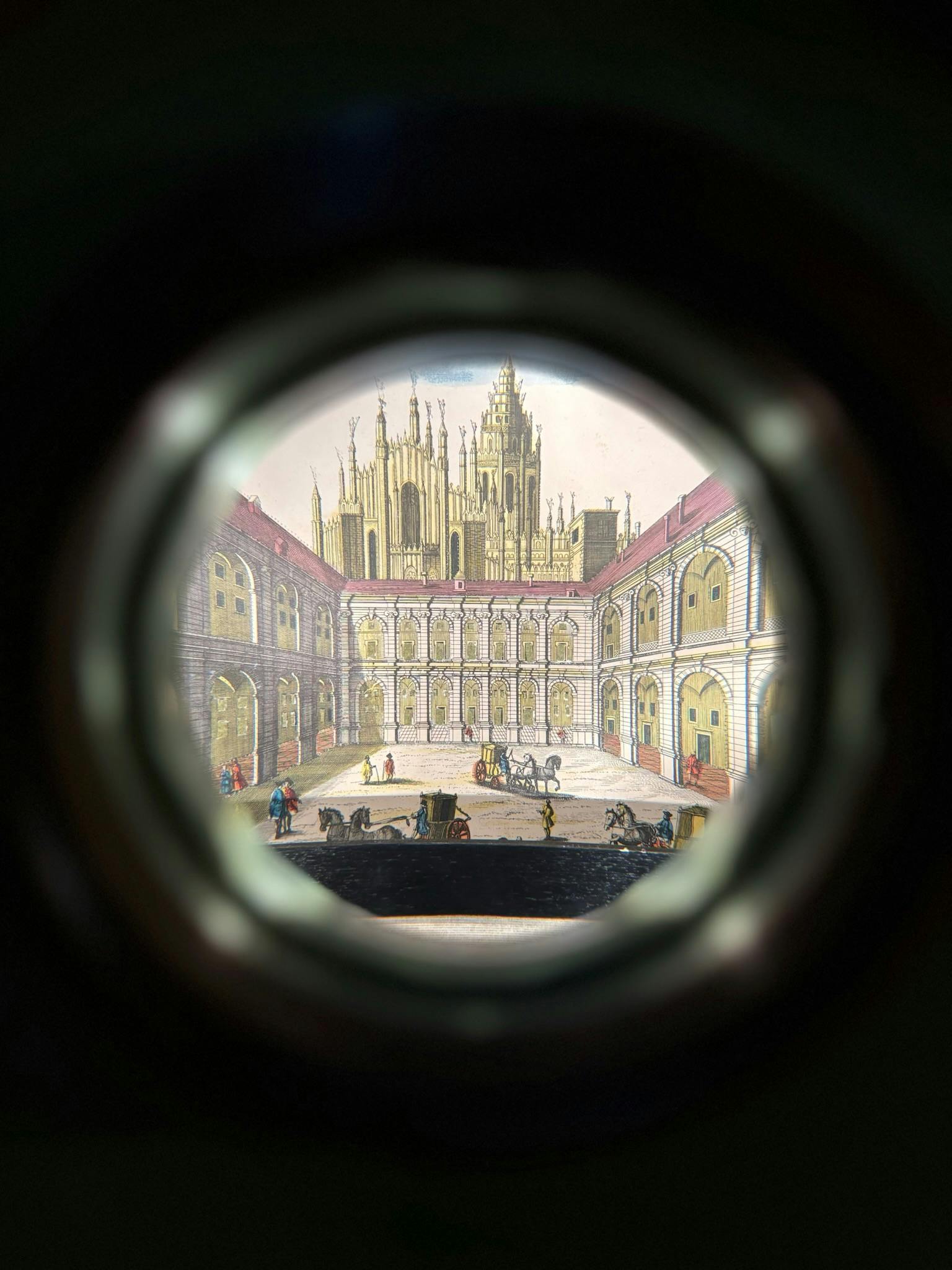

According to its protagonist’s memoirs, this story began in Venice, in the 1970s, in an attic overlooking Mercerie del Capitello (but the entrance is in Calle delle Ballotte). Laura was in her thirties and was rummaging in the attic of her childhood home. As I read her words, I pictured her as her eyes alighted on a box made of fancy wood with a long, flashy camera lens barrel on one face. The adjacent face had a small door that you could stick your hand in. At the top, there was a small metal exhaust pipe. This was all rather bulky, but the 1800s technical features – switches, snap-fit joints, closures, screws, glass panes – made the machine sophisticated and extravagant. What could it be? Laura also found a box of little hand-painted glass slides. They were about four inches tall and showed scenes and landscapes. She picked everything up and brought it to the living room. She shortly found out that the box was a lantern and could project the color images of the slides on the wall (if the room was dark enough). A magic lantern. Then, states Laura, everything changed. It was the “time = 0” moment when an idea blossoms and opens up a universe of opportunity. Laura abandoned fine arts and geometric abstraction – the world she had known until then – and chose to become a lanternist: one who, in a 50-year career, would create an archive of over 10,000 magic lantern slides and a collection of projection instruments that gave birth to a small but surprising museum in Padua. So what exactly does a lanternist do?

Projection glass, view

Fishing for fish in London City

Laura’s son, Carlo Alberto – currently the director of the museum and a professor in Film History and History and Technology of Photography at the University of Padua – remembers the long journeys to take his mother to her shows, with the lantern and slides carried in his car cabin thanks to a special permit. Then there was that night in London… a three-hour cab ride to seek out little fish: projectable fish. Shortly before, Laura had found an ancient double slide, and upon taking a closer look, she realized it was a minuscule magic lantern aquarium. It was an amplifier of wonder: when Laura inserted it into her two-lens lantern, the first barrel projected a nature background, and the other – with the special double slide – projected insects or small fish onto the background. This resulted in an impressive live projection of moving pictures: it was a forefather of live streaming. Therefore, on the evening when Laura had a show at the London headquarters of the Magic Lantern Society, she and Carlo Alberto drove around for three hours in search of suitable, real-life little fish. The crowd was thrilled. At the end of the show, the plane ride back home put the fish’s destiny on the line. The members of the Magic Lantern Society thus decided to organize an impromptu auction and the fish-actors soon found a home.

Laura Minici Zotti with a Magic Lantern

Darkness in the hallway of the stalls

In the collective memory, this story begins in 1975, in Prato, Italy. Laura was practicing to become a skillful lanternist and began to work on her shows – such as magic lantern versions of classic fables, which she developed by collecting slides of European capital sights, exotic characters, romantic landscapes, and phantasmagorias of ghosts and skeletons. Yet, back then, magic lanterns and the pre-cinema were unknown to most people. In 1975, Prato hosted the 11th Salone Internazionale del Comics e Cinema di Animazione (international comics and animated film convention), and Laura’s contacts and friends of contacts included the organizer, who discovered the magic of lanterns and invited Laura to make her first-ever projection before a large audience. As she walked on stage for a rehearsal, she found that Teatro del Giglio, the theater where she was set to perform, was full of obstacles. Bringing the images into focus was complex. She was on the proscenium, between the lantern and the screen. The directors of the opening night, sitting in the stalls, asked her to maintain a specific position, then another, then move one way, then make gestures she had never made. The lantern is a complex device requiring a special technique. You must respect the rhythm of the story and cannot easily distort it. There was an argument. In the end, Laura was relegated to the back of the projection screen, upstage. The projection could be seen, but not the magic lantern (nor Laura). It would be the first and last time: from that day on, Laura would always project from the crossing row, between the seats, in the darkness of the theater, among the people. To enjoy their amazement.

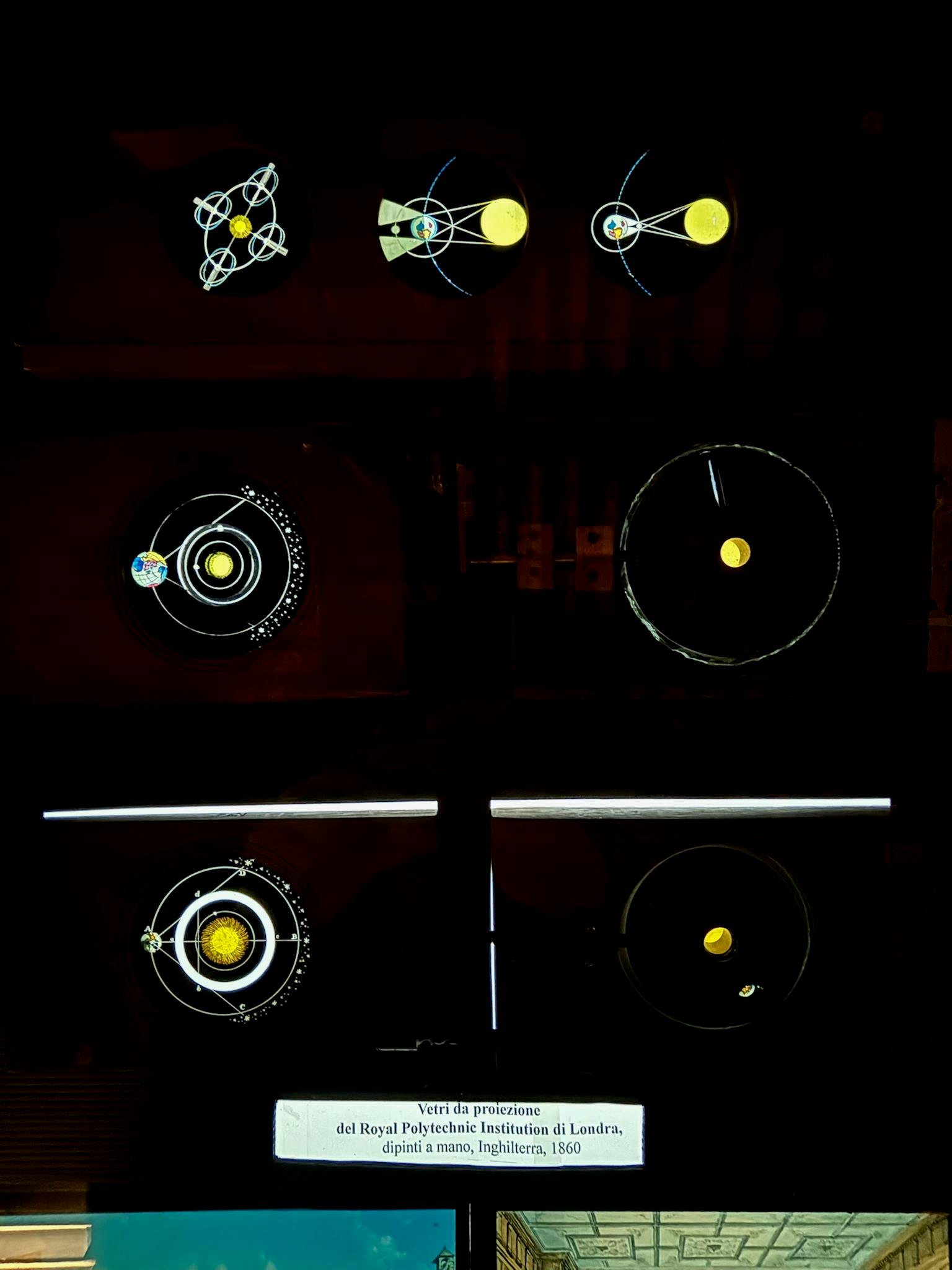

Projection glasses from the Royal Polytechnic Institution of London, hand-painted, England, 1860

Fragile memories, unpredictable futures

At one point, I asked Laura: do you still project? No, I am too old and it’s hard work, she answered. But she did put on a show last month and the next one will be, she says, in the springtime. Perhaps in Venice, where it all began. The birthplace (of her passion). And what about your slide collection? I asked. Are you still expanding it? No, not anymore, she said. When did you purchase your last piece? It is on the way from the UK, replied Andrei, the museum curator, from his desk. Laura’s face lit up. She told me that the slide shows the façade of Ca’ D’Oro, on the Grand Canal, with and without the balcony. It would be perfect for this spring’s show, she said: Venice in the age of the lantern. I made her promise to invite me.

I only had a short conversation with Laura, but I would still say that I don’t see her as a person who is obsessed with the past. True, she has dedicated a lifetime to a disappearing technique, she established a museum, she is the archivist and safe keeper of unique cultural heritage, and she is a collector of ingenious technology and improbable projection devices made before the cinematograph. Yet, I believe she is definitely forward-looking.

I say this because beyond her roles – museophile, archivist, collector – which are, by definition, the ones played by devotees of the past, Laura sees herself as a professional lanternist (perhaps the last one in Italy). What she does is work, not just passion. And like every professional, Laura is fully immersed in the present and naturally inclined towards the future.

Oftentimes, archives preserve frail stories – dozens of thousands of little hand-painted glass traces. When you gather them and organize them as archives, the footprints of people become a collective memory. If, instead, they shatter into pieces, the information becomes fragmented and the meaning is lost.

Laura’s archive is well-established and safe. It is protected by the museum and the Padua city administration. But Alberto is worried: Laura has never had a true apprentice. The sophisticated magic lantern projection technique, the job – which is not the passion – is destined to vanish.

Unless this article becomes that same moment in the attic for someone else: the “t = 0” moment, the starting point when an idea is born and opens up a universe of opportunity. Who will the next lanternist be?

Toy Magic Lanterns