The Case for Human Centered Design

Why Olivetti (and its humanist approach to business) is still relevant today.

What’s wrong with humanity?

As I scroll my feed and read the news, it seems like there is increasing disdain for humans as a whole. On a certain level, I get it. Humanity has fundamentally transformed the planet Earth. We’ve repurposed its resources for our own comfort and in the process harmed the living beings around us. We’ve caused mass extinction events, global warming, nuclear horrors. The list is seemingly endless.

Humanity’s role on planet Earth has been under attack for some time now. Anthropocentrism, a term coined in the 1890’s, is the belief that humans occupy the central role in the universe. To be clear, the idea that humanity was the protagonist of all of life long predates the coinage of anthropocentrism. It was only in 1859 when Darwin published his theory of evolution that this idea was properly challenged. That humanity might simply be an organism which had evolved from primordial ooze was new and shocking to society. Suddenly, humanity was just another species; “anthropocentrism” was used to criticize philosophical or scientific theories which falsely separated humanity from our fellow animals.

Yet, somehow, I feel we have lost touch with what it means to be human. I wonder if doing so could help us become better stewards of this planet, a planet which we as a species are increasingly capable of reshaping at will. As praise of human centered design is eclipsed by accusations of anthropocentrism, I am concerned that we are no longer concerned with the well being of the individuals who constitute the society in which we live.

When did human become such a bad word?

Earlier this month, Brian Thompson, the CEO of UnitedHealthcare, was murdered on a New York street in broad daylight. Such a striking act of violence would normally be condemned by society, but UnitedHealthcare has had such a negative impact on the lives of so many Americans that many people have taken to social media to praise the killer, Luigi Mangione.

UHC is a perfect example of a system ostensibly designed to care for human needs, twisted by greed. Health insurance was intended to be a social safety net, a form of financial support during a trying time. To fall ill, seriously ill, is harrowing enough. To know that your medical bills would be covered in the case of such a crisis is perhaps a small comfort, but a comfort nonetheless. In America, the system is broken. If you’re uninsured, the medical bills are astronomical. Even those who have an insurance plan live in fear, because if an insurance company decides they don’t want to cover the treatment needed to live, a serious illness can mean choosing between medical debt or death. Meanwhile, the CEOs of these health insurance companies make the big bucks: Brian Thompson made $10 million a year, plus benefits.

As I think about UnitedHealthCare, I wonder: is it possible to organize businesses so that they provide valuable services to society, care for their workers, and benefit the surrounding community, humanity, even Earth as a whole? What would such a company look like?

A company that comes to mind is Olivetti.

Is it possible to organize businesses so that they provide valuable services to society, care for their workers, and benefit the surrounding community, humanity, even Earth as a whole? What would such a company look like?

Founded in 1908, Olivetti is an Italian company best known for the Lettera 22, their iconic portable typewriter; their elegant writing machines were used by Cormac McCarthy, Sylvia Plath, John Updike, and Thomas Pynchon, among others, to compose their work. Now the brand has sunk into obscurity, but they were once world famous for their design work, providing inspiration for Steve Jobs during his time at Apple. IBM would send spies to check out their factories and stores to imitate their methods. They helped get man on the moon: NASA’s engineers used Olivetti’s P101, one of the first programmable calculators, in their work on the Apollo 11 mission. Their impact was widespread.

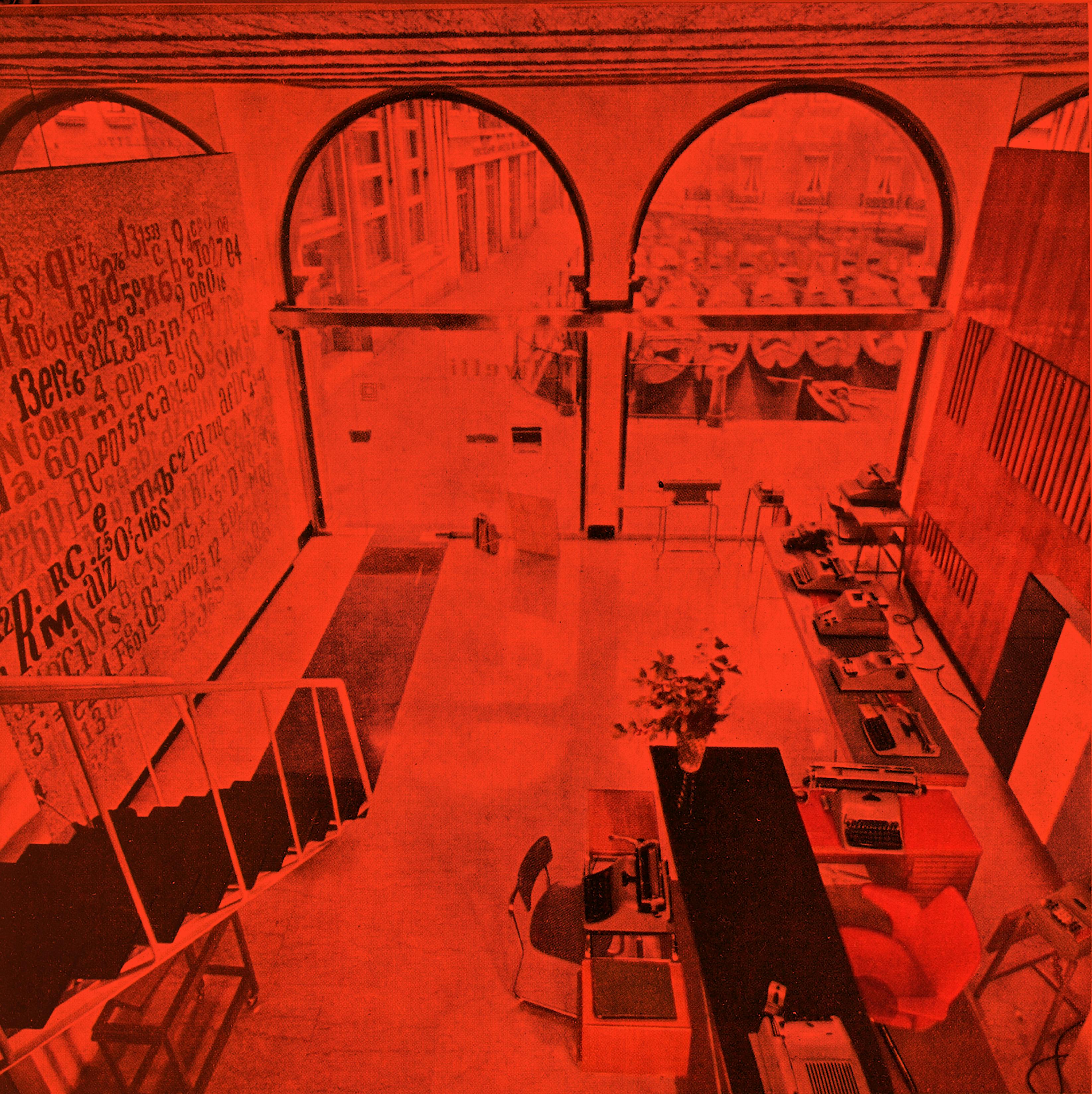

Unlike many contemporary corporations, Olivetti was not solely oriented around maximizing profits at all costs: taking care of their employees’ needs was a crucial part of the way the business was run. Camillo Olivetti, the eponymous founder, was a socialist and made sure to pay the workers in his factory well. Camillo’s son, Adriano, inherited his father’s humanist ideals and modernized them. He was fascinated by the architect Le Corbusier, who advocated for human centered design, and asked him to visit the factories to discuss how they might be improved. Adriano had worked in the factories when he was young and found the experience miserable - the factories were poorly lit and ventilated. Inspired by Le Corbusier’s belief that the design of buildings should be adapted to the needs of the humans who inhabited them, he hired a group of up-and-coming Italian architects to redesign the factories to make work as pleasant as possible.

It was Adriano’s love of architecture that first drew me into the brand. I took a trip to Venice for the Biennale Architettura with an architect friend; while we were in town, he wanted to check out Olivetti’s former storefront, which was designed by Carlo Scarpa. The space has been converted into a sort of memorial for Olivetti, but at the time, I didn’t engage with the history of the brand; instead, I was blown away by the beauty of the design and the lavish attention to detail. The work was clearly expensive, but also done with great care. The store, I thought, must have communicated the values of Olivetti to customers, that they were willing to put in the time and effort to create beautiful things that would last.

La Fabbrica e la comunità (Courtesy of Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti, Ivrea, Italy)

Funnily enough, it was later that day, exploring Venice, when I wandered into the Laguna~B shop, intrigued after I spotted their collection of books on design. I don’t remember the exact name of the book I picked up in Laguna~B, but it was something about design and ecology, something related to this idea that’s been trendy for a bit now, this idea that you need to consider more than just the function of a building, or a product, you need to think about the impact it will have on the environment, how people and other creatures will interact with it, its place within the world. Nothing exists in isolation, we’re all so connected, increasingly so.

These ideas about ecologies were floating around my head when I finally visited the town in which Olivetti was born. When Andrea Capra, a literary scholar, invited me to accompany him on a research trip to Olivetti’s factories in Ivrea, I told him I had never heard of the company before. It was only when looking through their archives that I saw a photo of the shop in Venice and finally made the connection. During the tour, we saw the beautiful factories that Adriano had designed for his workers. Our tour guide, Gianmaria Baro, told us that Adriano believed that work, in and of itself, could not provide a deep sense of fulfillment with life. He felt humans need art to be truly satisfied, and so he filled Olivetti’s work spaces with libraries stocked with modern literature, paintings by contemporary artists, and hosted regular concerts for the workers and surrounding community.

Adriano believed that work, in and of itself, could not provide a deep sense of fulfillment with life.

Adriano was not content to merely purchase art: he often played the role of patron. Walking around Ivrea listening to Gianmaria wax poetic about the glory days of Olivetti, I was reminded of Lorenzo il Magnifico — Lorenzo the Magnificent — the semi-benevolent tyrant of Florence who, during the Renaissance, cultivated artists like Michelangelo and Botticelli, among others. Lorenzo was influenced by the Neoplatonic humanist ideals that helped give birth to the Renaissance. The Neoplatonic worldview was fundamentally anthropocentric: many philosophers of the time believed that humans were divine beings, that humans had a type of soul which differentiated them from the beasts of the earth. Despite this, they argued that all of the world emanated from the divine, and some of the first thinkers to defend the rights of animals come from the Neoplatonic tradition. One could argue that valuing humanity, in all senses of the word, is likely to lead to a greater appreciation for all forms of life.

In Olivetti’s case, that seemed to be true. Though the architects who designed Olivetti’s buildings were practicing human centered design, they included large, open gardens which supported the local flora and fauna.

I’m still figuring out how I feel about Olivetti, the company. While it did so much good for the world, it also collapsed after Adriano died suddenly of a heart attack. Florence too suffered after the death of Lorenzo: the other members of the Medici family who grasped the reins of power afterwards were far less benevolent and the Florentines rose up in rebellion to cast them out of power. Still, though, I think the humanist ideals embodied by Olivetti resulted in a better life for their employees, their families, and the surrounding community. As we humans discuss how to manage our stewardship of the Earth, the ecological system that we inhabit, we should strive to integrate these humanist ideals into our model. How best to do that? After all this writing, I think looking at companies like Olivetti will be important as we consider humanity’s changing role in the world. We’re more capable than ever of shaping the Earth to our desires — what shape do we want it to take?

Further Reading:

- The Mysterious Affair at Olivetti: IBM, the CIA, and the Cold War Conspiracy to Shut Down Production of the World's First Desktop Computer

- Invented Edens : Techno-cities of the Twentieth Century

- Are We Human?: The Archeology of Design

Liara Roux is a multi-hyphenate artist, writer, political organizer, and human rights activist. Their research and editorial work focuses on design, sex and power dynamics in the modern world and was published in The New York Times, Washington Post, Interview, Motherboard, PIN-UP, and Dazed. Their first book, Whore of New York: A Confession, was released in 2021. We met her a couple of years ago when she visited our store in Venice, and we’ve kept in touch ever since. In 2023, we interviewed her in an episode of our discontinued column Lost Coordinates. @liararoux

Asilo Olivetti di Villetta Casana (Courtesy of Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti, Ivrea, Italy)

Further Reading:

- The Mysterious Affair at Olivetti: IBM, the CIA, and the Cold War Conspiracy to Shut Down Production of the World's First Desktop Computer

- Invented Edens : Techno-cities of the Twentieth Century

- Are We Human?: The Archeology of Design

Liara Roux is a multi-hyphenate artist, writer, political organizer, and human rights activist. Their research and editorial work focuses on design, sex and power dynamics in the modern world and was published in The New York Times, Washington Post, Interview, Motherboard, PIN-UP, and Dazed. Their first book, Whore of New York: A Confession, was released in 2021. We met her a couple of years ago when she visited our store in Venice, and we’ve kept in touch ever since. In 2023, we interviewed her in an episode of our discontinued column Lost Coordinates. @liararoux